Counting Crosswords, Part 1

Jul 03, 2020

An incredibly useless but very fun side project.

Last year, some friends and I got really into crossword puzzles and set out to construct a puzzle for the New York Times. I can’t get into details, but the puzzle idea required finding a crossword grid that satisfied a strict set of constraints. The search for this grid turned into an unnecessarily-complicated-but-really-fun coding project with some cool extensions. It’s been a year but I’ve been really bored during quarantine, so figured I might as well write it up!

What defines a valid crossword grid?

A New York Times crossword puzzle typically satisfies the following conditions:

- The white squares are fully connected.

- It is rotationally symmetric. This means the first row should be the reverse of the last row, the second row should be the reverse of the second-to-last row, etc. And the middle row is a palindrome, i.e. the reverse of itself.

- Every square must be in both a down and an across answer, and every answer must be at least three letters long.

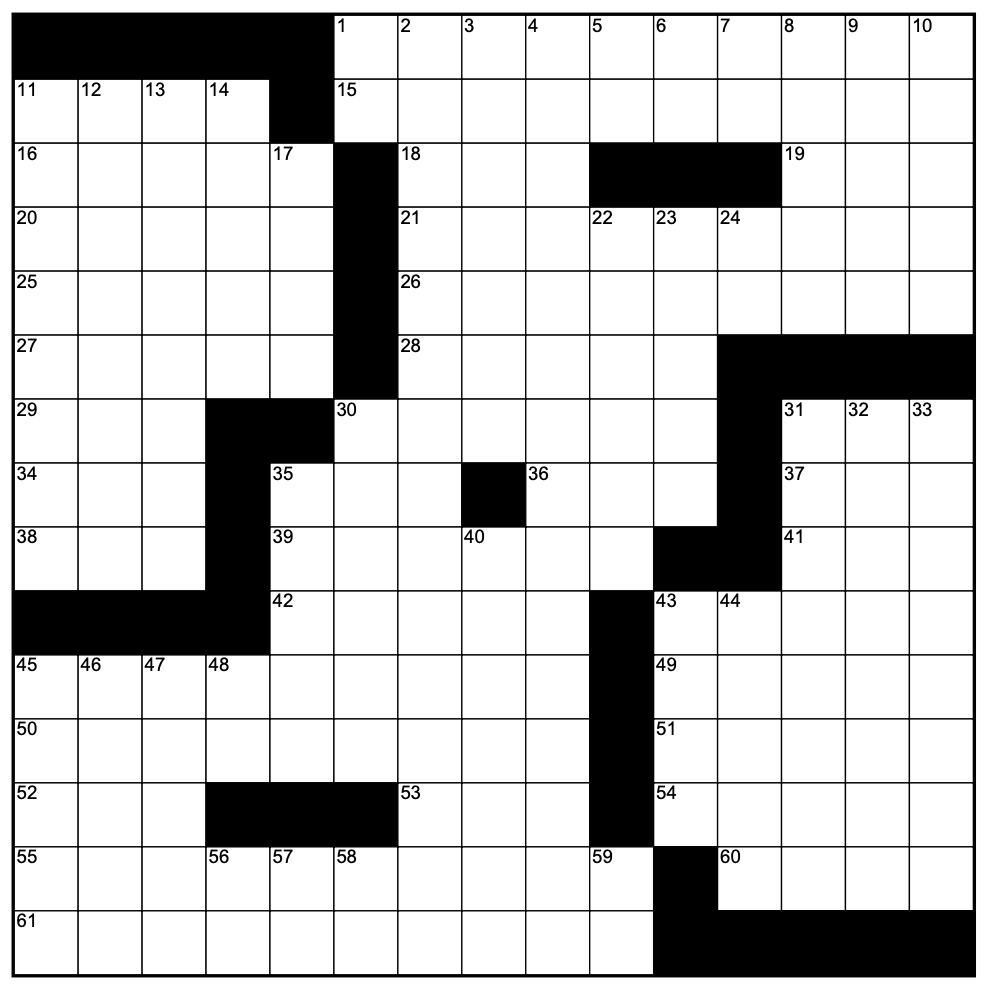

For example, the following grid is invalid because the white squares aren’t fully connected:

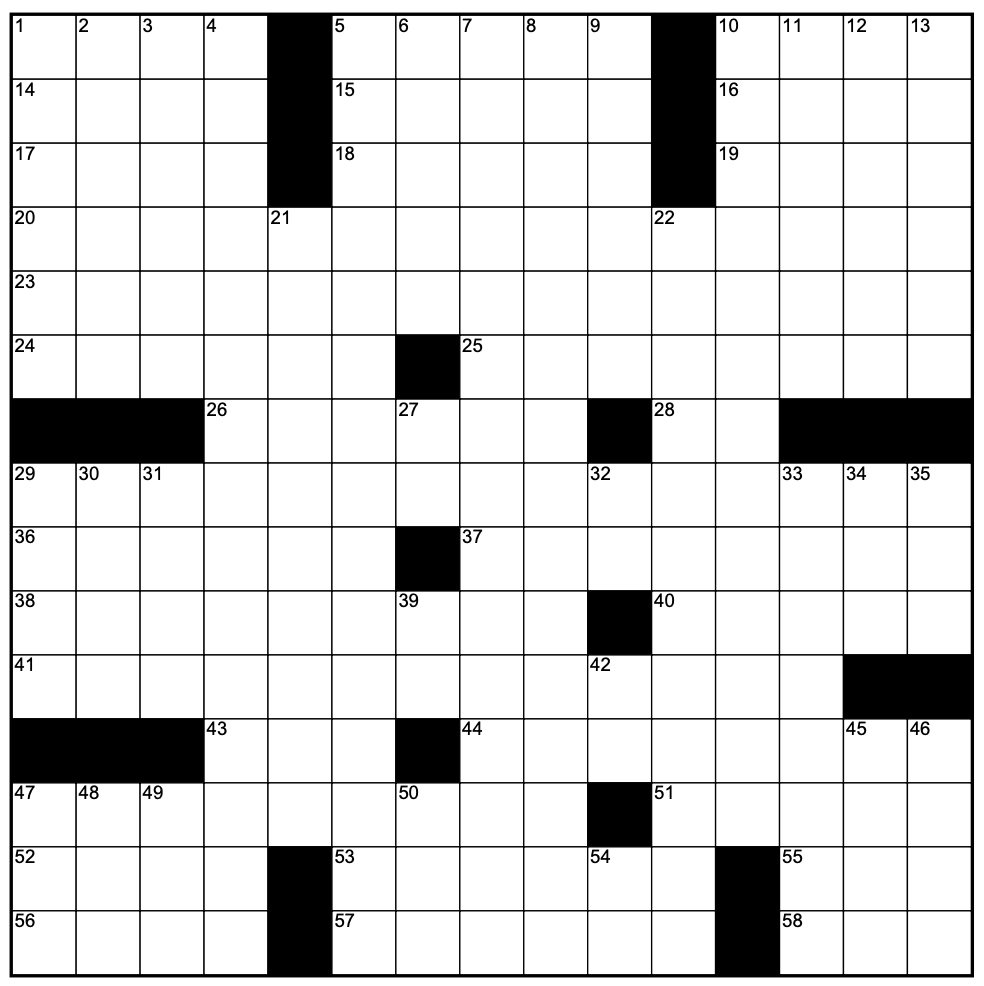

The following grid is connected, but it isn’t rotationally symmetric:

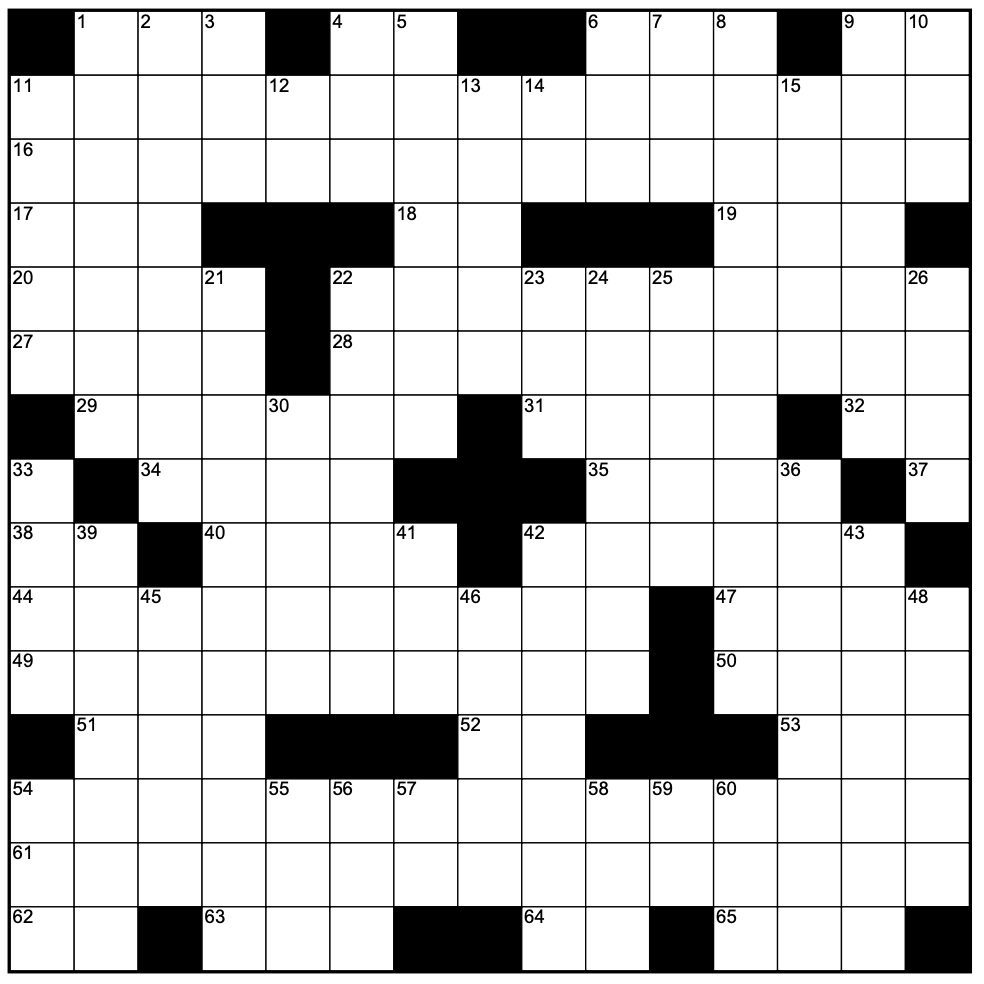

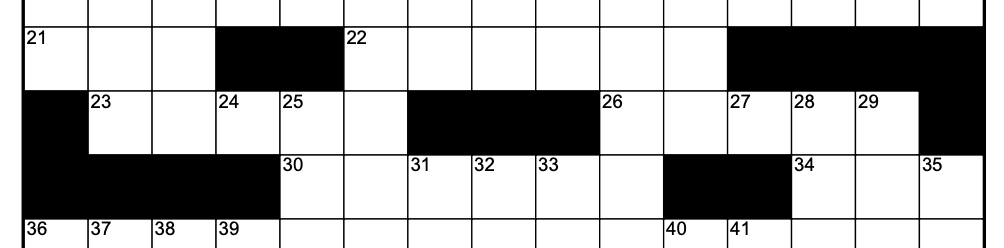

And the following is connected and rotationally symmetric, but has one and two-letter answers (like 37-Across and 57-Down):

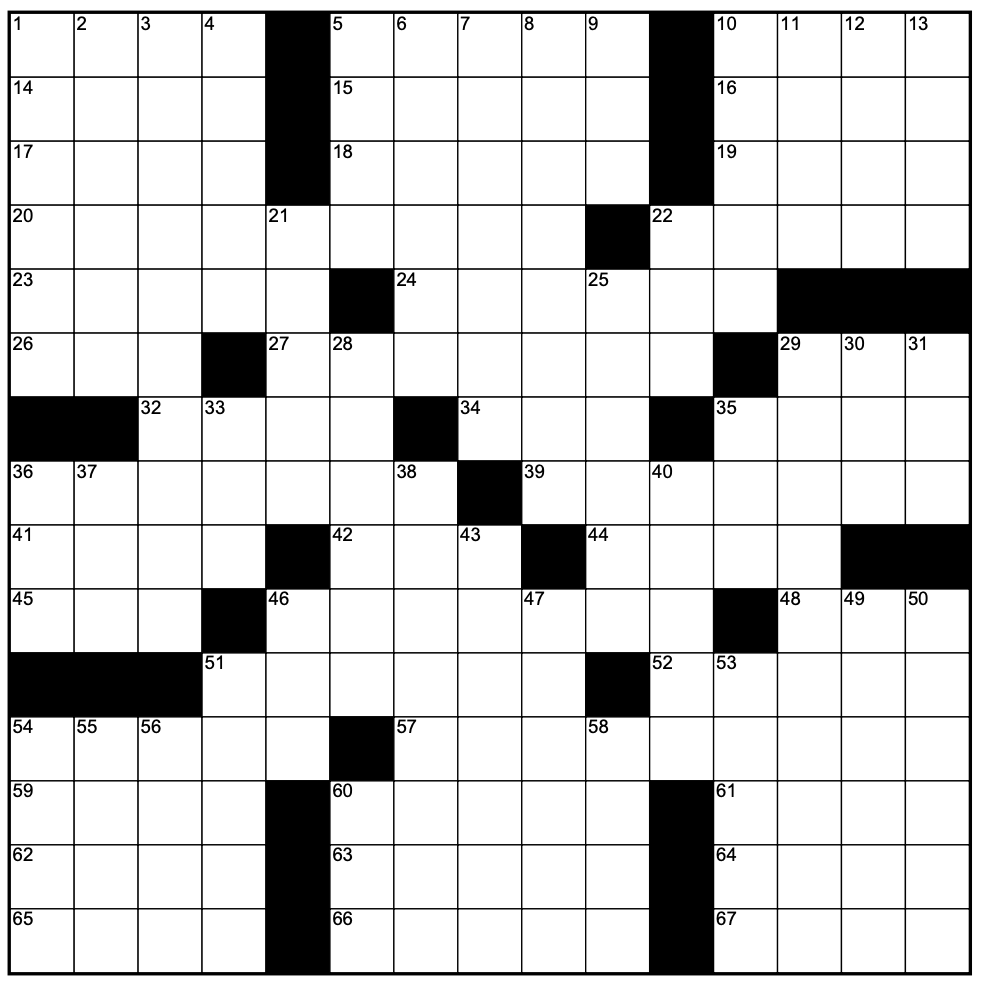

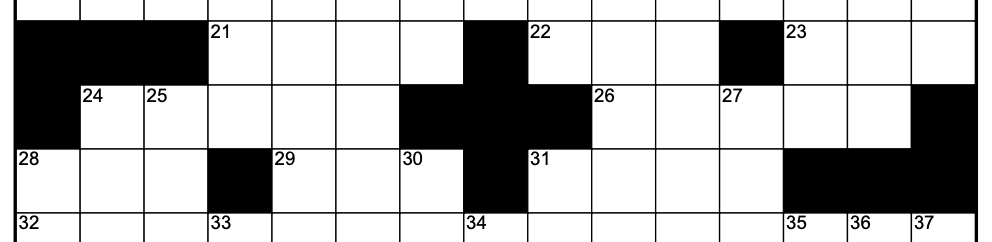

The following grid satisfies all the conditions:

The New York Times usually runs 15x15 puzzles on weekdays and 21x21 puzzles on weekends. Since we wanted to write a weekday puzzle, we focused on 15x15 grids. Note that even though we’re working with a fixed-size grid, we can still express algorithmic complexity in terms of \(n\), where \(n\) is the width of the grid.

Generating Crossword Puzzles

Alright, so we needed to generate valid 15x15 crossword grids and check a set of special conditions. It turns out these conditions were extremely rare, so performance was critical. In this section, I’ll go through different iterations of the algorithm, describing the optimizations that eventually brought us to an acceptable state. This isn’t exactly the order in which we arrived at the solution, but it’s close.

Take 1: Python and Chill

We started off with a Python program that generated grids one square at a time. The pseudocode was something like this:

- Represent each square using a boolean:

Trueis black,Falseis white. Rather than store a two-dimensional 15x15 array, we concatenate the rows and represent each grid as a length-225 array. - Recursively generate rotationally symmetric grids by filling in the first \(113 = \lceil 225/2 \rceil\) values with every combination of

TrueandFalse. Set the remaining 112 values to the reverse of the first 112. - For every grid, check the following conditions:

- Check the three-letter minimum. In other words, a consecutive run of

Falsevalues in any row or column must have length at least 3. - Run a depth-first search on the white squares to ensure connectedness.

- Also check some “obvious” conditions: for example, the grid can’t have all-black rows or columns (otherwise it wouldn’t really be a 15x15 grid).

- Check the three-letter minimum. In other words, a consecutive run of

- If everything looks good, check the special conditions.

Of course, we weren’t trying to generate every possible 15x15 grid: just enough that we’d run into one that satisfied all the conditions. However, we were generating these grids so naively that a very, very small percentage of generated grids even made it to Step 4–perhaps one or two every minute. Of the grids that passed Step 4, we couldn’t find any that really worked: they were too sparse, or it’d be too hard to fill them with English words.

To tally things up:

- This algorithm generates \(O(2^{n^2/2})\) candidate grids.

- Checking all the conditions (DFS, clue-length, all-black, etc.) takes \(O(n^2)\) time.

- Each grid takes \(O(n^2)\) space.

To get this to work, we needed to take a smarter approach.

Take 2: One Row at a Time

Generating grids square by square was doomed to fail because the conditions depend on the relationship between squares–it made more sense to think in terms of rows. This way, we could eliminate invalid rows from the get-go: in fact, of the \(2^{15} = 32,768\) possible rows, less than 800 satisfy the three-letter minimum!

I don’t know the exact solution, but it’s safe to say the number of valid rows is \(O(c^n)\) for some value of \(c < 2\). I computed this for \(n = 5, 6, 7, \dots 20\) (see A130578) and the ratio between consecutive terms indicates \(c \approx 1.6\).

(We also pruned rows that weren’t practically feasible, for example those with more than four black squares in a row. This reduces \(c\) even more.)

So now our algorithm looked like this:

- Precompute all valid rows. As a special case, also precompute valid palindromic rows to account for the middle row. This takes \(O(2^n)\) time, but it’s a one-time thing so no worries.

- Fill in the first 8 rows of the crossword, and set the last 7 rows to the reverse of the first 7.

- Check vertical clue lengths, run the DFS check, and check special conditions.

Now we’re looking at something like \(O((1.6^n)^{n/2}) = O(1.6^{n^2/2})\) candidate grids. Decreasing the base of the exponent is a huge improvement.

Take 3: Considering Columns

We could improve this algorithm by only adding rows that satisfy the three-letter minimum vertically. Because the middle three rows are so constrained, it helps to start from the middle row then move towards the edge. Recall that the 8th row is a palindrome, and the 7th and 9th rows are reverses of each other.

For example, the following isn’t allowed:

But this is:

With that in mind, here’s the new algorithm:

- Precompute valid rows.

- For every possible 8th row, find all valid 7th rows.

- For the 6th row, only consider rows that satisfy the three-letter minimum with rows 7 through 9. Continue this until the edge of the grid. Note that the first three rows have special restrictions because they’re near the edge.

- Do the DFS check.

- Check special conditions.

I’ve lost track of how many grids make it to Step 4, but it’s probably \(O(c^{n^2/2})\) for an even smaller value of \(c\). However, calculating the next row is an inefficient operation: we need to iterate through all valid rows, and do an \(O(n)\) check for each one. It’d be nice if we could precompute things.

Take 4: “Go”ing a “Bit” Crazy

We were beginning to reach the limits of this grid representation: boolean arrays weren’t fun to work with, and we couldn’t precompute too much because it’s so space-inefficient.

The solution: instead of booleans, treat each square as a bit! We can fit each row in a 16-bit integer, so our new grid representation is simply an array of 15 uint16 values. How nice. To implement this, a measly Python program wasn’t going to cut it. We needed to take things to the next level.

(Okay, in retrospect I’m not convinced that we needed to: like, if I ran the program for long enough I’m sure we would have found a grid that worked. But the project had transcended this one crossword puzzle, and had become something much deeper. Or I was going insane.)

Anyways, I rewrote the whole thing in Go. It’d been a few years, and I wanted to brush up. Go also made it easier to implement Grid Representation 2.0.

Now we can precompute valid rows as a list of uint16 values, letting 1 and 0 represent black and white, respectively. For instance, \(100001100010000_2 = 17168\) is a valid row, but \(101001100010111_2 = 21271\) isn’t. We can also compute a map reverse where reverse[x] stores the bitwise reverse of row x: this makes it easier to fill the bottom half of the grid.

So given three rows a, b, and c, how do we calculate all possible next rows x? It might help to look at a diagram:

a 100011100010000

b 000000000110001

c 100000100010001

x 000001000100000

We have a one-letter answer whenever there’s a column with 101 in rows b, c, and x. In other words, if b & ~c & x has any ones (where & is bitwise AND, and ~ is bitwise negation), then we’re in trouble. This means we must have b & ~c & x == 0, and similarly we must have a & ~b & ~c & x == 0 to avoid any two-letter answers. Combining these two, it follows that [(b & ~c) | (a & ~b & ~c)] & x == 0, or [(a | b) & ~c] & x == 0 after simplifying the Boolean logic (hopefully this makes intuitive sense).

Awesome! So we can precompute a map avoidOneOne where, for all uint16 values j, avoidOneOne[j] stores every row k satisfying j & k == 0. This means j and k don’t have any 1 bits in the same position, hence the name. Therefore, x is simply the set of values in avoidOneOne[(a | b) & ~c].

Note that we have to treat the last three rows carefully. Consider the following:

d 100011100010000

e 000000000110001

f 100000100010001

EDGE ---------------

If there’s a column ending in 10 or 100, then we violate the three-letter minimum. In other words, we must have e & ~f == 0 and d & ~e & ~f == 0 . To deal with this, we can precompute another map avoidOneZero, where avoidOneZero[j] stores all k satisfying j & ~k == 0 (the values here are simply the bitwise negations of the values in avoidOneOne).

If avoidOneOne and avoidOneZero stored a list of uint16 values for every j, we’d need to write some nontrivial logic to intersect the two lists. We can expedite this by storing bitarrays instead! Go has a bitarray package that supports sparse bitarrays, so this was pretty easy to implement.

Here’s our hyper-optimized algorithm:

- Precompute all valid rows.

- Precompute

reverse,avoidOneOneandavoidOneZero. - For every possible value of Row 8 (

r8), consider values ofr7satisfyingr7 & ~r8 & reverse[r7] == 0. Can’t have a101in the middle three rows! - Use

avoidOneOneandavoidOneZeroto compute the possibilities for the remaining rows. - Turn candidate grids into a two-dimensional array and do the DFS check.

- Check special conditions.

This helped a lot! We removed the \(O(n)\) check when evaluating rows, and the bithacks were wonderful. I don’t think we decreased the number of candidate grids, but we improved the constant factor significantly.

Take 5: Final Touches

To top things off, we added a few more optimizations: first, Go made it easy to parallelize the search. Simply create t goroutines and assign each thread a subset of the middle rows.

Second, we also cared about the number of words in the grid. Most NYT crossword grids have around 60-80 words–more than that looks ugly, and fewer than that is essentially impossible to fill. As amateur constructors, we were looking at the 70-80 range. I won’t get into details, but we figured out an \(O(n)\) method to compute this value using bithacks and precomputation. This way, we’d eliminate a majority of grids before the DFS check. (Hint: In every row or column, a new word starts when we move from from an edge/black square to a white square.)

And that’s it! The program was spitting out hundreds of grids every minute, and we eventually found one that worked. You can check out the source code, but it’s quite a mess.

The End of the Story

So we filled up the grid, wrote clues, and submitted it to the New York Times. Unfortunately, it got rejected–it’s an extremely slow and competitive process!–but we submitted a revision and are awaiting feedback.

…there’s more?

While working on this, I came across a FiveThirtyEight challenge that asked how many valid 15x15 New York Times crossword grids you can make. Unfortunately, this program wasn’t going to cut it: there’s no point in generating every grid if you’re just trying to count them. I’ll talk about this in Part 2!

Appendix: Space Complexity

So, what’s the memory overhead of avoidOneOne and avoidOneZero? They clearly have the same size, so we’ll focus on avoidOneOne. Let’s start with a loose upper bound: for a grid of size \(n\), there are \(2^n\) keys and at most \(2^n\) values in each bitarray, which makes an upper bound of \(2^n \cdot 2^n = 4^n\).

Okay, but we’re only storing rows in each bitarray, right? Using the value of \(c = 1.6\) from earlier, we get a tighter bound of \(2^n \cdot 1.6^n = 3.2^n\) (this is actually \(O(3.2^n)\), because our \(c^n\) bound wasn’t exact).

But let’s take a closer look at what avoidOneOne stores: again, for every value j, we’re storing all k satisfying j & k == 0, which means j and k don’t have any ones in the same place.

Consider a value j with \(x\) ones: there are \(\binom{n}{x}\) possible values of j. For each j, there are \(2^{n - x}\) values of k that work. This is because k has a zero wherever j has an one, and the remaining \(n-x\) bits have no constraints. Using the Binomial Theorem, we arrive at the following bound:

\[\begin{aligned}\sum_{x=0}^n \dbinom{n}{x} 2^{n-x} &= \sum_{x=0}^n \dbinom{n}{x} 1^x 2^{n-x} \cr\cr&= (1+2)^n \cr\cr &= 3^n \end{aligned}\]

This is even better, and we didn’t use the fact that the values are rows! In reality the space overhead is much, much smaller. This actually matters: \(4^{15}\) bits is around 135 megabytes, while \(3^{15}\) bits is smaller than 2 megabytes.

Share